search

date/time

| North East Post A Voice of the Free Press |

Andrew Liddle

Guest Writer

P.ublished 10th January 2026

frontpage

Opinion

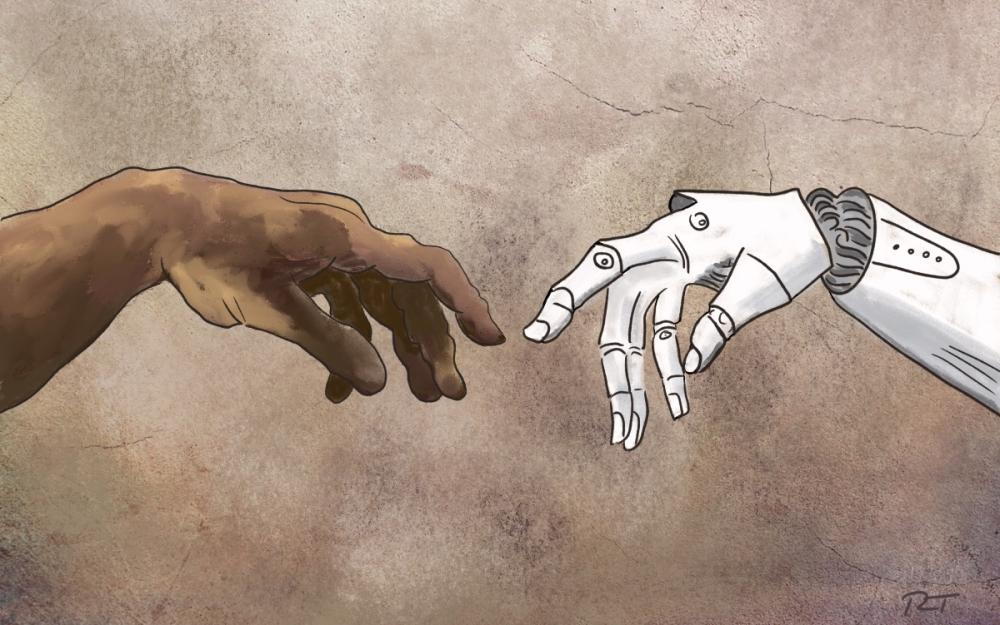

Living With The Machine: Why I Find AI Both Useful And Unsettling

Andrew Liddle can’t make up his mind about AI

And yet I remain uneasy.

I often ask myself whether I think AI is “good” or “bad”. Actually, I don’t find that question very helpful. AI isn’t a moral agent. It’s a tool — an extraordinarily powerful one — and like all tools it reflects the values, assumptions and incentives of those who design and deploy it. What matters is not what AI is, but how it is used, by whom, and to what ends.

At its best, AI feels like a great aid to human intelligence. It excels at pattern recognition, speed and scale. It doesn’t tire, lose focus or grow bored with repetition. That makes it exceptionally good at sifting data, spotting anomalies and handling routine tasks that once consumed vast amounts of human time. In medicine, it can flag up early signs of disease. In science, it accelerates research that might otherwise take years. In everyday life, it removes friction — making things quicker, smoother, more efficient.

There is something genuinely democratic and exciting about all that. Tools that once required specialist skills are becoming widely accessible. A small business can compete with a large one. A lone researcher can do the work of a team. Used well, AI can lower barriers, extend human capability and free us to focus on judgement, creativity and care — the things machines still at this stage cannot do.

But I’m increasingly conscious of how unevenly those benefits are distributed. AI systems are trained on the world as it is, not as we might wish it to be — and the world is biased, unequal and capable of being corrupted. When those distortions are absorbed into algorithms, they can be amplified at scale.

I don’t see this as a future risk because it’s already happening. Facial recognition systems that struggle with some skin tones, recruitment tools that replicate historic discrimination, predictive policing that reinforces existing patterns of surveillance — these outcomes may be embedded into data long before any line of code is written.

What troubles me further is that many AI systems famously make decisions that even their creators apparently struggle to fully explain. That might be tolerable when the stakes are low, but far less so when algorithms influence credit, employment, healthcare or liberty. I’m not comfortable with a world in which decisions of real consequence are made without clear lines of accountability and methods of scrutiny.

I often find myself wondering what earlier thinkers would have made of all this. Freud might have been fascinated — and disturbed — by our willingness to outsource memory, language and judgement, faculties once central to the self. Marx would surely have asked who owns these machines, who profits from their productivity, and what happens to value when human labour is displaced or rendered invisible.

Orwell, I suspect, would have recognised the dangers of algorithmic surveillance and managed consent — not control through force, but through nudging, ranking and quiet prediction. Even Hannah Arendt’s chill warnings about banal and thoughtless evil and responsibility (as set out in Eichmann in Jerusalem) feels newly relevant, as automated systems place decisions at a moral remove.

Work is where my concerns become most concrete. AI will not simply eliminate jobs in a neat or uniform way. It will reshape work profoundly — taking over some roles, deskilling others, and intensifying surveillance and productivity pressures on those that remain.

We’ve been here before, of course. Technological revolutions have often created more jobs than they destroyed, but rarely without long periods of disruption and social strain. This time, I worry less about mass unemployment than about a thinning of meaningful work and a growing sense of disposability.

Founding sociologists would have seen this as a core modern danger: not unemployment, but work that persists while losing meaning. Durkheim would call it anomie without job loss, Marx a deepening of alienation, Weber an updated iron cage, all symptoms of depression and frustration.

Even creative fields — once thought relatively safe — are feeling the pressure. AI can now generate text, music and images with startling fluency. I don’t believe machines are “creative” in any human sense, but markets may not care about that distinction. If creative output becomes endlessly replicable at near-zero cost, what happens to authorship, originality and reward? The danger isn’t that AI replaces human creativity, but that it devalues it.

There are environmental costs too, which receive far less attention than they should. Training large AI models consumes enormous amounts of energy and water. At a moment when climate change demands restraint and efficiency, the unchecked expansion of AI infrastructure feels like a contradiction we’ve yet to confront honestly.

Perhaps my deepest concern, though, is cognitive dependency. As machines take over more tasks — remembering, navigating, writing, deciding — I notice how easy it is to let judgement slip away. As a simple example, if I drive to somewhere using satnav, I don’t seem to learn how to get there as I would have without the device.

In a certain sense, tools that anticipate our needs can also narrow our choices. Recommendation systems already shape what we read, watch and buy. Convenience, taken too far, risks eroding agency.

None of this leads me to reject AI. That would be pointless, and probably hypocritical. I use it, and I benefit from it. But clearly we need transparency, accountability and public oversight. We need serious investment in education and retraining. And we need to protect spaces where human judgement and care remain central, even if they are not the most powerfully efficient.

Ten years from now, I suspect AI will no longer feel new at all. It will be embedded and largely invisible — woven into daily life much as electricity or the internet now are. The real question is whether it will be quietly serving human ends or insidiously reshaping them. We may look back on this moment as the point at which we insisted that speed and efficiency were not the only measures of progress. Or we may find that those choices were made for us, by default rather than design.

The future of AI won’t be decided by the limitations of discovery and technology, but by what we decide it should be allowed to do — and by how seriously we take the responsibility of living alongside it.

I don’t imagine a future in which machines suddenly take over in the manner of H.G. Wells’s fantasies, marching against us with malevolent metallic intent. The danger, as Wells himself understood, is subtler than that. It lies in drift and creep rather than domination — in systems that grow so useful, so efficient and so embedded that we stop questioning them altogether. The machines won’t need to conquer us if we gradually reorganise our lives around their priorities.

What matters, in the end, is not whether intelligence becomes artificial, but whether responsibility remains human. As Aristotle reminds us, “We are what we repeatedly do.”